The Deplete and Retreat team are delighted to be attending the first ever celebration for International Day of the Glacier in Paris, at the UNESCO HQ, in March 2025. We will be hosting a side event, entitled “A vanishing mountain cryosphere and its importance to the water cycle under climate change“, aimed at informing stakeholders and policymakers about the changing climate and glaciers of the Andes.

To celebrate the event, we’re delighted to have produced a policy brief, in both Spanish and English, documenting the impact of climate change on the glaciers, wetlands and water resources across all of the Andes.

Highlights

Glaciers, snow, permafrost, lakes and wetlands are natural reservoirs of water. They support communities across the Andes.

Andean glaciers are shrinking, and the rate of ice loss is accelerating. Andean glaciers are thinning by an average of 0.7 m per year, ~35% faster than the global average.

Climate change is raising air temperatures, decreasing snowfall and increasing droughts across the Andes.

Extreme weather events are likely to become more frequent and severe, with heat stress, forest fires, floods and landslides threatening local communities.

Under the highest emissions scenarios, projections show an almost total glacier loss in the Tropical Andes. Glaciers across the rest of the Andes will experience significant losses under an optimistic climate scenario, and up to 58% of the present ice volume will be lost under a higher emissions scenario.

Warming affects precipitation, snow and glaciers, which together control ecologically, socially and economically important high-altitude wetlands. These wetlands also have the potential to form an alternative water store as glacier snow and ice stores are depleted.

Glacier shrinkage and eventual disappearance will decrease downstream water availability, and could contribute to extreme droughts in the arid and semi-arid Andes, impacting food and water security to populations along the length of the Andes.

Adaptation strategies should be implemented by working together with affected communities, considering regional variations, and assessing the impact of glacier loss, alongside water demand and human vulnerabilities.

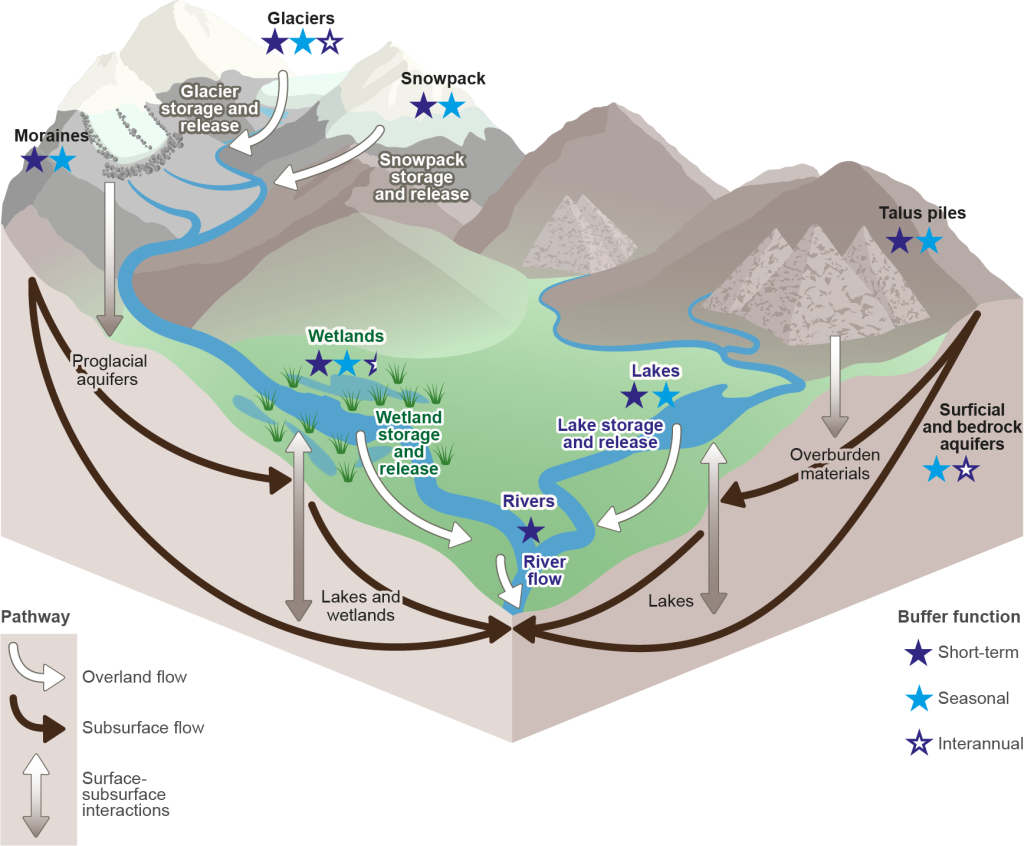

The water and food security of 90 million people depends on the Andean water tower

Mountain ranges force air upwards, resulting in cooling, condensation and precipitation. This precipitation is captured and stored in snow, glacier and permafrost ice, lakes and wetlands, and released slowly in the dry season in meltwater rivers (e.g. Figure 1), which is particularly significant in drought years [1]. The meltwater is used across the Andes for domestic consumption, hydroelectric power, industry, irrigation of arable crops and supporting livestock farming. Therefore, the viability of this water resource has ramifications for geopolitics, economics and biodiversity [2].

The warming climate is depleting these stores of snow and glacier ice. Warming air temperatures means that snow increasingly falls as rain, with shorter seasons of snowfall accumulation. Snowfall is also increasingly delivered in fewer, but more extreme, weather events [3].

As a result, the water stored in these reserves is depleting, threatening the ability of the mountain cryosphere to release water during the dry season. Changes in snow and glacier melt have high impacts on Andean rural populations, who have fewest resources and therefore have limited capacity to adapt to climate change. Land-use change and population growth is projected to increase demands for water over the coming decades [2].

The climate of the Andes

The Andean climate varies considerably due to its latitudinal span, dramatic elevational range, and the interplay between several large-scale climate systems and their interactions with local terrain (Figure 2).

Tropical Andes

In the tropical Andes (Figure 3), there is little variation in annual temperatures. Precipitation (rain and snow) varies seasonally and is heaviest on the eastern slopes around January (Figure 2). Rain and snow in the tropical and subtropical Andes are delivered by the South American monsoon system.

This is heavily influenced by the seasonal movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which migrates southward during the Southern Hemisphere summer. Climate variability in the tropical and subtropical Andes on annual and decadal timescales is therefore strongly influenced by changes in the ITCZ near the Equator.

El Niño Southern Oscillation

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) causes large interannual variations in precipitation patterns [4, 5]. El Niño years bring high temperatures across most of the Andes, but variable precipitation patterns with drier wet seasons in the Peruvian Andes and wetter and colder springs in the mid-latitudes [6]. El Niño years can lead to increased glacier melt, with warmer temperatures driving higher snowlines [7].

Southern Andes

The Southern Andes have a seasonal temperature cycle with colder winters. Westerly winds bring storms and peak precipitation around June [4].

Climate is influenced by the Southern Annular Mode (SAM) [6] (Figure 2), which influences the strength and positioning of the moisture-bearing Southern Westerly Winds. This controls the delivery of snow to mid-latitude and southerly Andean glaciers.

A warming climate

Global climate models project temperatures will increase between 1.1 °C and 4.5 °C by the end of the century across the Andes. Changes to precipitation are more spatially varied, with increases in precipitation over the Peruvian Andes of 1.8 % to 3.3 % compared with a decrease in the Chilean and Argentinian Andes of 1.9 % to 12.4 % [8].

Patterns of warming temperatures and precipitation change will lead to a decrease in snowfall, in line with other mountain regions across the world [9], but the magnitude and spatial variability is broadly unknown. Uncertainty is especially large in the Andes, where the precipitation amounts and type (snow, rain or hail) are strongly modulated by the interactions between changing large-scale atmospheric circulation (Figure 2) and local orographic processes. This is further complicated by a lack of detailed modelling studies and observational data.

Due to climatic, geographical and societal differences, climate risks and hazards caused by extreme events vary along the Andes. In the tropical Andes heat stress, droughts, floods, landslides, and forest fires are the most prominent threats. The southern Andes face challenges such as prolonged droughts, extreme precipitation and floods from atmospheric rivers, and cold surges [3].

Many of these hazards are likely to increase in frequency and intensity in the future due to the projected changes in temperature and precipitation and resultant glacier shrinkage

The Andean glaciers

The largest glacierised area in the Southern Hemisphere

There are ~25,000 glaciers in the Andes, covering an area of ~30,000 km2 [10], with an estimated volume of 1,006 km3 [11]. This is the largest glacierised area in the Southern Hemisphere outside the Antarctic ice sheet [12]. These Andean glaciers supply water for a large proportion of the population in Andean countries [13]. Glaciers extend from 11°N to 55°S, across multiple climate zones [14] (Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6). These glaciers form an important water resource for local populations all along the Andes.

Tropical Andes

In the Tropical Andes between 11°N and 17°S, glaciers are restricted to very high altitudes, and are characterised by year-long melt, associated with warm air temperatures and extremely high radiation levels. High solar radiation here means that any snow falling away from the glacier melts very quickly (Figure 3), emphasising the importance glaciers play in providing water in the dry season [15]. Besides glaciers, water is also stored as frozen ice in the permafrost table, an increasingly important water resource as aridity rises.

Dry Andes

In the Dry Andes between 17°S and 31°S (Figure 4), glaciers form in desert conditions. Precipitation originates from the Atlantic, mostly driven by easterlies associated with the South American monsoon system [16]. From ~27°S, winter westerlies from the Pacific bring some snowcover. Low precipitation results in small numbers and extents of glaciers, despite the high elevation (Figure 5). Here, ice-rich permafrost is the most extensive ice reserve.

Further south, in the Central Chilean and Argentinian Andes (31°S to 35°S), precipitation is derived from the Pacific, with winter precipitation sustaining a larger glacier concentration and ice volume, with greater seasonally snow-covered areas, providing a more substantial and important water reserve for local communities.

Wet Andes

The Wet Andes extend from 35°S to 55°S and contain glaciers sustained by the Westerlies (Figure 2; Figure 4). The behaviour of these glaciers is subject to changes in the Southern Annular Mode. In the Northern Patagonian Andes, glaciers occur on higher mountains and volcanoes, but from 45°S to 55°S, the larger snowfall volume supports large icefields, the largest of which are the Northern and Southern Patagonian icefields.

Glacier Retreat

Around ~350 years ago, during the period known as the ‘Little Ice Age’, Andean glaciers were much larger than at present. Since the end of the Little Ice Age, and with the advent of industrialisation, glaciers in the Andes have lost around 25 % of their overall area [17].

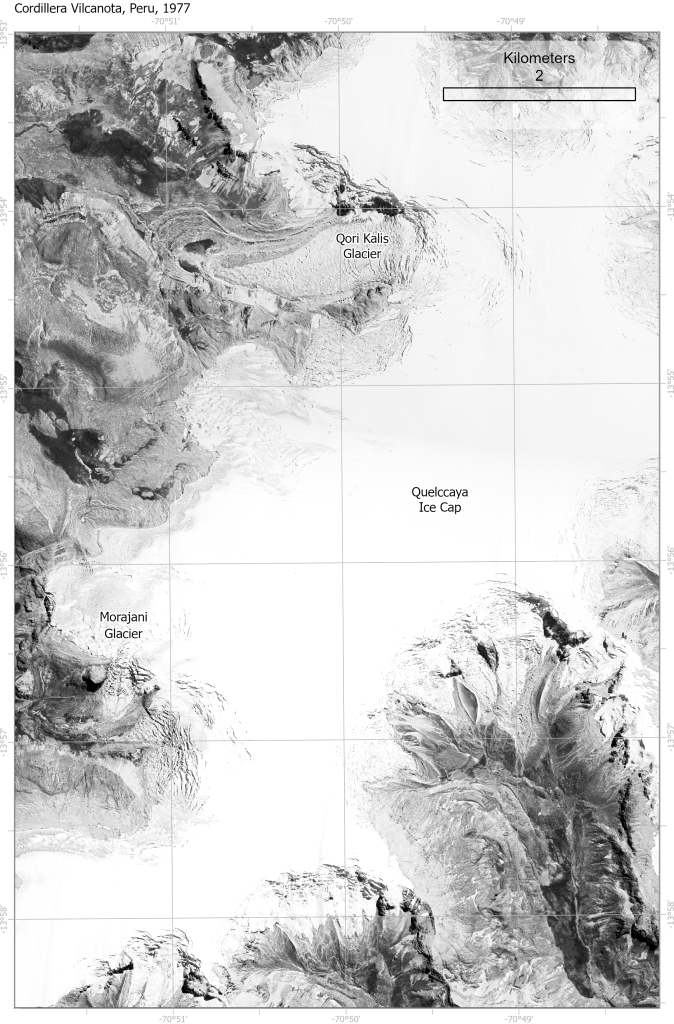

Between the 1970s and the present day, the terminus of many glaciers has receded by hundreds of metres to kilometres, with 10 km retreat observed at Upsala Glacier in the Southern Patagonian Icefield, and 1.2 km of retreat observed at the tropical Qori Kalis Glacier in Peru (Figure 7, overleaf).

The rate of change has accelerated in recent decades with unprecedented rates of ice loss post-2000. An up-to ten-fold increase in the rate of ice loss after the year 2000 has coincided with increased greenhouse gas emissions.

Today, Andean glaciers are ubiquitously receding, thinning more quickly (-0.69 m yr-1) than the global average (-0.46 m yr-1) [18]. Tropical glaciers in the low latitudes are especially threatened and are losing a substantial portion of their remaining ice, to the point that some have become extinct.

Projections of future glacier change

Even under optimistic climate scenarios of drastic reductions in greenhouse gases (low emissions scenarios, such as RCP2.6), projections show that tropical glaciers are likely to lose between 30-98% of their ice by 2100, with glaciers across the rest of the southern Andes also experiencing significant losses (~8-35%; [19]).

If emissions continue to rise under a less optimistic climate scenario (RCP8.5), glacier ice loss will increase, projected to be between ~70-100% and ~30-58% for the low latitude and southern Andes, respectively.

Preservation of many low latitude glaciers is likely an insurmountable challenge: recent projections of a +2°C warming scenario show that the Tropical Andes will be entirely, or almost entirely, ice free by 2100 [20].

Such loss of ice across the Andes will increase the stress on freshwater resources relied upon by communities and major cities downstream, especially during periods of drought

Figure 7. Examples of glacier retreat from Quelccaya Ice Cap, Cordillera Vilcanota, Peru. Left side: Hexagon KH-9 satellite imagery. Right side: Sentinel 2A satellite imagery, with glacier outlines for the Little Ice Age [17], 1977, 2003 [10] and 2022. Glacier recession in metres, 1977-2022, is shown with the white bars. Glacier names and locations shown in Figure 4.

High Andean wetlands

High Andean wetlands, locally known as bofedales, occonales or vegas (Figure 8), are vital to the local environment, acting as water and carbon reservoirs, biodiversity hotspots, and as cultural and economic landmarks for indigenous and local pastoralist communities. In the tropical Andes, these wetlands are an essential component of local pastoralist production systems, and therefore are highly managed by local high Andean pastoralist communities.

Vulnerable Andean wetlands

As glaciers retreat, two critical questions emerge: Does the reducing glacial meltwater as glaciers shrink threaten wetland survival? And can wetlands serve as alternative water sources, ensuring water security in a glacier-free future?

The impact of glacier loss on Andean wetlands remains debated. Wetlands farther from glaciers are primarily sustained by precipitation and glacier-independent groundwater, showing little response to glacier retreat [21]. In contrast, wetlands near glaciers rely heavily on glacier melt for their sustenance (e.g. Figure 8c), making them highly vulnerable to glacial recession [22, 23].

The role of wetlands in downstream water availability is complex due to spatial and temporal variations in their water sources. Studies report that wetland contributions to runoff can range from less than 10% [24] to over 75% [25] of total streamflow, depending on the region.

Despite these discrepancies, there is strong consensus that wetlands buffer low flows during dry seasons, enhancing water availability when other sources become scarcer [24, 25]. These wetlands can therefore be an important component of climate change adaptation in the seasonally dry high tropical Andes.

Potential for climate change adaptation and mitigation

As glaciers, permafrost and snowfields lose their ability to store and release water, wetlands become increasingly critical as alternative water reserves. Beyond glacier retreat, however, human activities such as road construction, overgrazing, and water extraction for mining and domestic use threaten these ecosystems and their hydrological functions [26]. Alternatively, effective management and irrigation by local pastoralist communities can support wetlands.

Protecting Andean wetlands and understanding their connection to glacier loss and streamflow regulation is essential for quantifying and securing future water resources in the region.

Water resources in a changing water tower

Glacier shrinkage and ‘Peak water’

The reduction and potential disappearance of glaciers will significantly impact downstream water availability. ‘Peak water’, the point of maximum glacier melt, is a turning point where hydrological processes shift, affecting water security. While some Andean regions will still see rising glacier melt before freshwater supply declines, others have already passed ‘peak water’ and are experiencing reduced meltwater resources due to glacier shrinkage [27].

Glacier meltwater and droughts

The consequences of this reduction in glacial meltwater for water availability vary over time and space, and depend on the interaction between stores of water in glaciers, snow, wetlands and groundwater (Figure 9). For example, in the Tropical and Dry Andes, glacier and snowmelt provide crucial water sources, especially during droughts, contributing up to 90% of streamflow in dry seasons.

In the wetter southern Andes, glacier melt plays a minor role compared to rainfall, making these regions less vulnerable to glacier recession and meltwater reduction. However, severe drought periods can change this picture, and glaciers currently offer a secure water resource.

Drought periods also influence the importance of glacier melt contributions along the length of the rivers. The impact of glacier retreat typically diminishes downstream, where human water use is often less affected, except during droughts, when glacier snow and ice reservoirs become essential as alternative water suppliers [1]. This crucial role of glacier melt is threatened as glaciers retreat and pass peak water.

Adaptation and mitigation

While stopping individual glacier shrinkage locally is unrealistic, measures can mitigate reduced meltwater impacts. Effective strategies must consider regional variations, from the northern to southern Andes and upstream to downstream, and should consider the various natural flows and stores of water through the system (Figure 9). In addition, the magnitude of effects also depends on affected communities and their means to implement mitigation and adaptation strategies [28].

Risks to future water security across the Andes are a consequence of both human and natural systems and of changing supply and demand. As glaciers shrink, supply diminishes. Concurrently, demand from humans is increasing and water use patterns are changing.

Author list

Davies, B.J., Becker, R., Bhattacharjee, S., Bradley, S., King, O., Potter, E., Lee, E., Andrade, M., Ávila, F., Baiker, J.R., Bendle, J., Borrell, L., Bozkurt, D., Bravo, C., Buytaert, W., Calle, J., Carrivick, J.L., Cuadros-Adriazola, J., Curry, C.S., Drenkhan, F., Dussaillant, A., Dussaillant, I., Edwards, T., Falaschi, D., Fox, E., García, J-L., Gribbin, T., Gonzalez, M., Huss, M., Innes-Jones, L., Irarrazaval, I., Jones, J., Li, S., Masiokas, M., Matthews, T., Maussion, F., McNabb, R., Montoya, N., Nicholson, L., Paschalis, A., Pellitero, R., Perry, B., Pitte, P., Rabatel, A., Reid, B., Somos-Valenzuela, M., Soruco, A., Ticona, L., Velarde, F., Vuille, M., Ely, J.

Funding information

This policy brief was funded by the UKRI NERC Project “Deplete and Retreat: the future of the Andean water towers” (NE/X004031/1) and by Newcastle University.